We continue to ignore massive pensions elephant in the room

The national debt is likely to go up by more than €40 billion within next two years

The Irish Times editorial of November 13th on the topic of pensions referred to the establishment of a Pensions Commission born of a need to delay a difficult decision when the current Government was being formed.

The difficult decision was whether to allow the already decided age increase for the social welfare pension from 66 to 67 to stand. Pending the commission’s report, it stays at age 66.

The gross cost involved is about €400 million.The net amount, of course, is substantially less – firstly income tax is deducted and then VAT plus excise is recovered when the money is spent. In fact, given that unemployment or some other benefit is usually paid immediately to anyone retiring at age 65, the true cost could be close to zero. But it has given rise to a commission, already with 11 members and with more seeking to join.

This all ignores the real elephant in the room,which is the already enormous accrued cost of pensions, both for the public sector and for social welfare beneficiaries who have paid contributions all their working lives. It is against a background where pensions have been paid out by the State largely on a pay-as-you-go basis, with almost no fund built up and an ageing population.

A future workforce will have to support a growing number of pensioners. These pension costs were not suddenly discovered when the present Government was being formed.

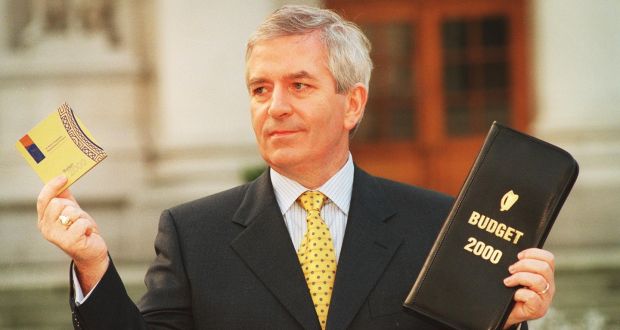

Following a report on pensions in the late 1990s, the then minister for finance Charlie McCreevy decided that something would have to be done to cope with this growing liability and set up the National Pensions Reserve Fund (under the umbrella of the National Treasury Management Agency).

Financial return

The legislation establishing it provided that it would be “for the purpose of meeting as much as possible of the cost to the exchequer of social welfare pensions and public service pensions to be paid from the year 2025 until the year 2055”.

The fund was to be controlled and invested by an independent commission, which included prominent international experts – Dan Tully, former chairman and chief executive of Merrill Lynch; Dr Martin Kohlhausen, chair and former CEO of Commerzbank; and Don Roth, former treasurer of the World Bank.

The obligation on the commission was to secure the optimal total financial return for the fund, subject to an acceptable level of risk. The fund was kick-started with proceeds from the privatisation of Telecom Éireann of about €4 billion, and a contribution equivalent to 1 per cent of GNP was to be paid in each year from the exchequer.

By law, no money was to be taken out of the fund before 2025. Most of the money was invested internationally, mainly to ensure that the investments would be protected if something were to go wrong with the Irish economy (a good decision, given what happened post the 2008 financial crash).

It was agreed, however,to put up €200 million towards the cost of the Eastern Bypass to complete the ring road around Dublin.

The fund soon gained an international reputation and other countries were very interested in how it was established. Indeed,the chairman of the then newly-formed Chinese National Council for Social Security Fund, Mr Xiang Huaicheng, a former minister for finance of China and currently chairman of the China Development Institute, headed a delegation to Dublin and spent several days learning all about how we had set up the fund.

We had calculated that if the rates of return earned on the fund in its early days had continued, it would have accumulated to about €140 billion by 2025. Even that enormous sum would only have covered about two-thirds of the estimated pension liability that would have accrued by 2025. As things turned out, zero interest rates would have meant that the net present value of the pension liabilities will be much greater while the return on the fund would have been smaller.

The rot started in 2009 when the minister for finance wanted the fund to invest in the two major Irish banks – AIB and Bank of Ireland. As such investments did not meet an acceptable level of risk, the law was changed to enable him to direct the commission to invest €3.5 billion in preference shares issued by the banks.

By the time I left the NTMA at the end of 2009,the fund totalled €22.3 billion. A later minister for finance, Michael Noonan, abolished the fund entirely at the end of 2014 and transferred the remaining balance into the Ireland Strategic Investment Fund. It is not clear if this could be used to meet some pension liabilities in the future.

So now we have an enormous pension liability and almost no assets to meet the costs. Future generations will have to pick up the tab, both for current pensioners and those still working now, while trying to make provision for their own pensions.

But that’s not all they will be paying for, as a result of Government spending this year, necessary and otherwise, from closing down the country.

The national debt is likely to go up by more than €40 billion in two years – this year and 2021 – almost as much as the €50 billion incurred from the foundation of the State to the end 2008. And that will not be the end of it, given the ongoing cost of the damage being done to the economy.

Final thought

With interest rates close to zero on Government debt (as the European Central Bank provides much of the funding), the interest bill has not been an issue recently. However, over time interest rates will rise, and even a modest rate on an enormous debt will hit the exchequer – and taxpayers – hard.

So we bequeath that also to future generations. I doubt they will thank us.

Could anything be done about it? The National Pensions Reserve Fund could be reconstituted. But the vision and the conviction to do something like this probably doesn’t exist.

A final thought. Years ago, when we were spending huge amounts on the public capital programme and it was delivering very little growth, I asked a German friend why Germany got growth but we couldn’t. His answer was that when a camera was to be made, the Germans got on and made it. In Ireland you write papers about it. Touché.